Wanderer

Can we find a music that is neither directly composed nor purely random? At times, the standard grid-based sequencer, for all its utility, becomes boring. And pure stochastic processes, while unpredictable and potentially novel, lack the kind of structure that makes music feel intentional. What’s interesting to me is something in between, a system that exhibits deterministic complexity, producing outputs that surprise even its creator while maintaining an inner coherence.

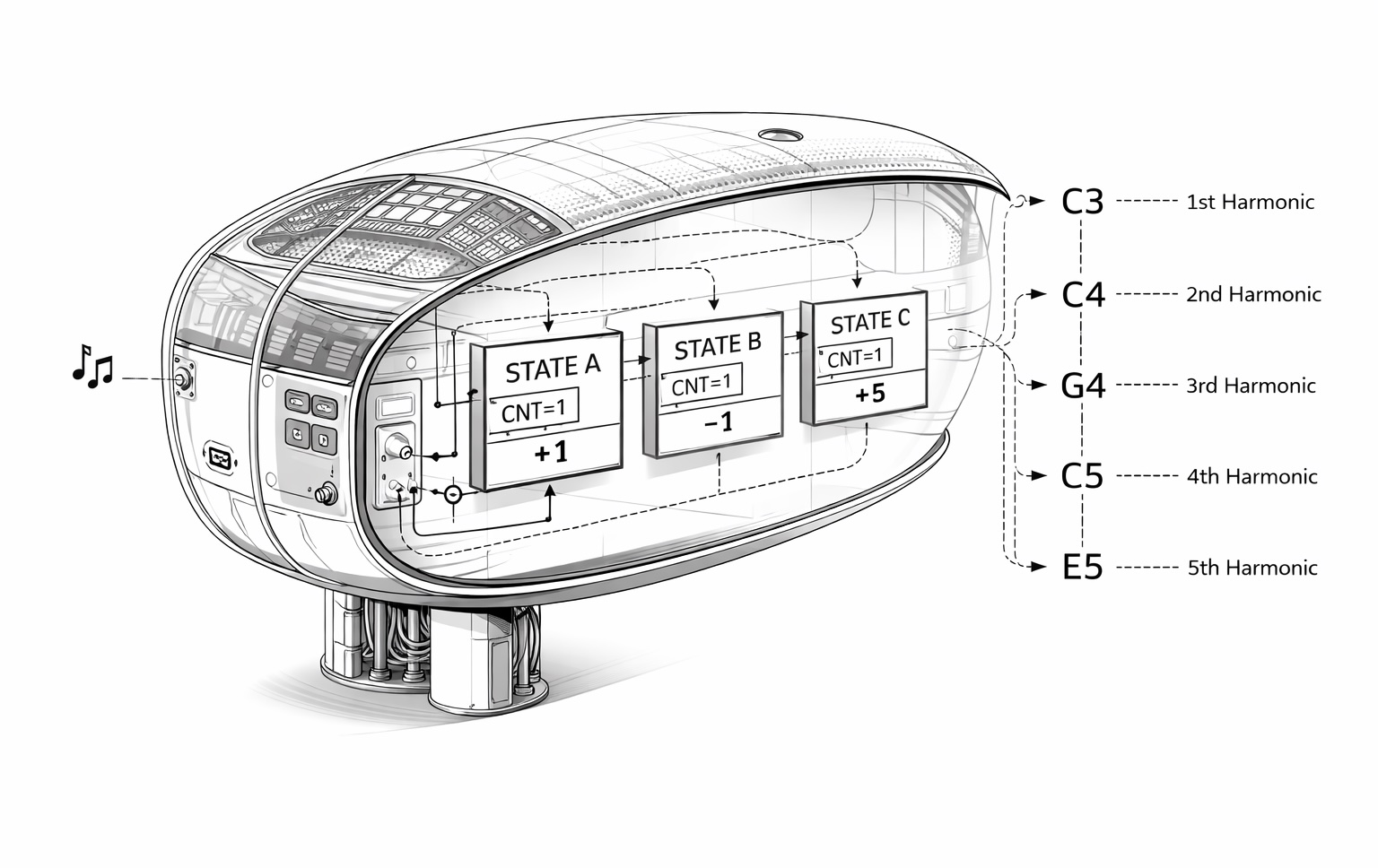

Wanderer is a small step in this direction. It’s a MIDI processor that transforms incoming notes into their harmonics, but the choice of which harmonic is governed by a counting automaton, a state machine that walks through a sequence of transformations, dwelling in each state for a variable number of steps before transitioning to the next.

The result is a kind of harmonic wandering. Feed it a single repeated note, and it returns a melodic line that feels almost composed. The input becomes a pulse, a heartbeat, while the output traces paths through the overtone series.

The Tyranny of Notes

There’s a phrase I have been guided by lately: the tyranny of notes. In traditional electronic performance, the performer is responsible for every pitch, every rhythm. But this creates an impossible situation. No human can match the complexity of the systems they’re controlling in real-time. The result is often a kind of theater, the performer appears to be playing, but the actual composition was determined long ago, frozen in a DAW timeline.

What if this relationship were inverted? Let the machine handle the notes, the discrete, quantized decisions about pitch, while the human focuses on timbre, texture, dynamics. The performer becomes a translator, interpreting the machine’s output through the continuous, analog domain of sound shaping.

Wanderer is an experiment in this direction. The note sequence emerges from the interaction between input timing and the automaton’s internal state. The performer’s job is to decide what those notes sound like.

A Detour: Counting Automata

A finite automaton is a state machine: it exists in one of several states, and transitions between them according to fixed rules. Feed it an input, it produces an output and moves to a new state. Simple enough.

A counting automaton adds a wrinkle. Each state has a threshold, a count that must be reached before the transition occurs. So the machine might stay in state A for three steps, then move to state B for one step, then to state C for two steps, and so on. The same input produces different outputs depending on where you are in the count.

This is different from randomness. The sequence is entirely deterministic, run it twice with the same inputs, you get the same outputs. But the layered thresholds create patterns that are difficult to predict by inspection. The complexity emerges from the interaction of simple rules.

@dataclass

class State:

counter: int

threshold: int

operator: str

operand: intEach state in Wanderer’s automaton carries an operator and operand that modify an accumulating value. State A might add 1, state B might subtract 1, state C might add 5. The value determines which harmonic gets applied to the incoming note.

def step(self):

self.current_state.counter += 1

if self.current_state.counter >= self.current_state.threshold:

self.current_state.counter = 0

self.current_state = self.transition_matrix[self.current_state]

self.value = self.apply_op(self.current_state.operator)

return self.valueRun this for a hundred steps and a sequence emerges that feels almost melodic, rising, falling, dwelling, jumping. Not random. Not composed. Something else.

Harmonics as Material

The overtone series is one of those places where physics and perception align in uncanny ways. A vibrating string produces not just its fundamental frequency but integer multiples: the octave, the fifth, the next octave, the major third, and so on. These are the harmonics, and they’re encoded in the timbres we hear every day.

Wanderer uses the first eight harmonics, converted to semitone offsets:

self.harmonics = [

int(round(12 * math.log2(n), 2)) for n in range(1, n_harmonics + 1)

]

# Result: [0, 12, 19, 24, 28, 31, 34, 36]The automaton’s output value, taken modulo 8, selects which harmonic to apply. So a C3 input might become C3 (fundamental), C4 (octave), G4 (fifth), C5 (two octaves), E5 (major third), and so on, depending entirely on where the automaton happens to be in its cycle.

Architecture

The system is deliberately minimal. A Python script creates virtual MIDI ports that appear in any DAW. Notes flow in, get processed, flow out. Hot-reloading allows the automaton to be tweaked while music plays.

┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐ ┌─────────────┐

│ DAW │─────▶│ Wanderer │─────▶│ Synth │

│ (source) │ MIDI │ (process) │ MIDI │ (sound) │

└─────────────┘ └─────────────┘ └─────────────┘Each MIDI channel gets its own processor instance. This matters for polyphonic behavior, four input notes on four channels, each wandering through the harmonic series on its own trajectory. There’s potential here for a kind of analog quartet: four voices, each following deterministic but distinct paths, occasionally converging on consonance before drifting apart.

What Emerges

The audio sample in the repository demonstrates the simplest case: a few repeated notes transformed by the automaton. What emerges sounds intentional, there are phrases, a sense of direction, moments of tension and resolution. None of it was composed. Initial conditions were set and the system ran.

This is what makes deterministic complexity interesting. The patterns aren’t random, but they’re also not predictable in the way a composed melody is predictable. They exist in a strange middle ground, coherent enough to feel meaningful, unpredictable enough to surprise.

There’s a connection here to what Sergi Jordà calls the essential role of nonlinearity in musical instruments, and what Chris Kiefer, building on Jordà, terms “uncontrol” in his work on Echo State Networks. The performer doesn’t directly control the output, but they’re not entirely passive either. They’re navigating a system, responding to its behavior, shaping it through the parameters they can influence. The machine isn’t a tool exactly. It’s more like a collaborator with its own logic.

Next Steps

The current automaton is hardcoded, four states with fixed thresholds and operators. The obvious extension is to make these configurable, perhaps seeded by MIDI channel or velocity. Using the initial note velocity to set the thresholds would make the system responsive to performance dynamics.

There’s also the question of visualization. The automaton’s state wants to be visible as it runs, which state, what count, which harmonic. Something terminal-aesthetic, maybe a radar chart with each angle representing a state. The system already prints its state to the console:

01 | • 60 → 72 | 01 | + 01 | 01 | [00] 12 19 24 28 31 34 36But there’s something more to be done here. The behavior wants to be seen as well as heard.

This project is part of a larger exploration I am calling Flow Control, an investigation into deterministic systems that produce emergent musical behavior. The neural sequencers, the small network experiments, and now the counting automata are all probes into the same territory: what happens when computation handles the notes, and human attention focuses on everything else?

Source: github.com/lucaskuzma/wanderer